You’re probably familiar with the Archibald Prize – Australia’s famous portrait prize – but alongside it each year there’s a landscape prize: the Wynne, and also the Sulman for things like still lives, everyday scenes, murals and depictions of mythology and religion.

I haven’t yet been but here’s a preview of how the theme of religion is represented in this year’s Sulman, and to sum up –

I think we are confronted with the elusive God and the elusive self.

In particular, let’s consider the work of two artists: Western Sydney artists, Marikit Santiago, pictured here with her husband for reasons that will become clear, and a well-established 80-year-old painter, Gareth Sansom.

You have until 10 January 2021 to take in this exhibition, so that’s lots of opportunity!

Sansom’s entry is ‘Looking for God in abstract art.' It’s a painting that gets more and more interesting the more you look. Christianity is present in words like faith and the letters INRI are the Latin summary initials of Jesus Christ King of the Jews.

But what to make of it all?

The painting is fragmented in style – flat, geometric shapes alongside painterly sketches, an unresolved sense of whether the work is depicting a flat surface or three dimensions.

Sansom states that his work 'interrogates the idea that God may or may not be present in any situation'.

His artist’s statement is thick with allusion: to an Ingmar Bergman film that takes its title from the book of Revelation and is considered a meditation on death and the silence of God.

Of the explicitly religious content, Sansom says that these may conjure up ideas about my own mortality at 80, or may be seen as red herrings within an abstract puzzle. The sense of puzzle and fragmentation is a feature of Sansom’s surreal and dada impulses and is also present in an earlier work: 'Looking for God in abstract art 1985.'

Sansom leaves us with a sense that looking for God is not going to be rewarding and may even be a foolish, false quest.

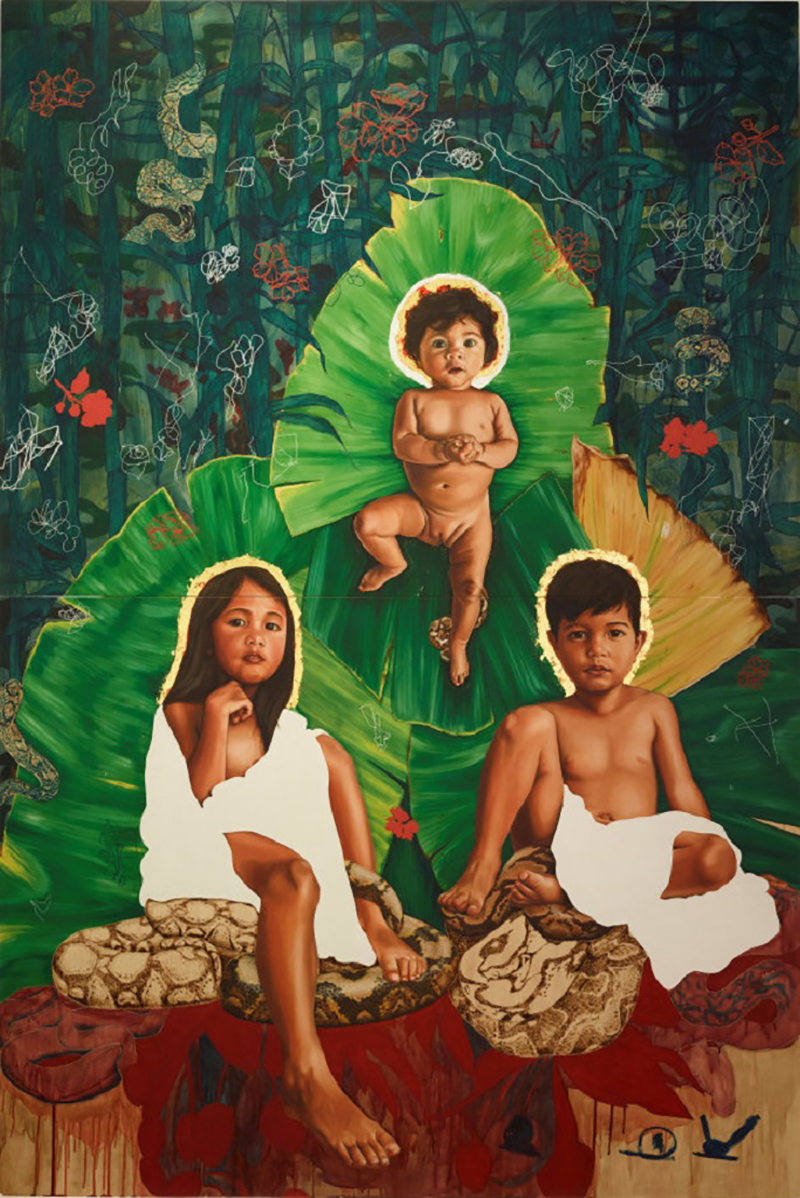

The winner of the Sulman this year is a work by Marikit Santiago, 'The Divine.'

This is a beautiful painting heavy with the conventions of devotional, Christian art. One can sense a Philipino Catholic heritage and it’s easy to create links to biblical and Christian thought as we see an Eden-like garden, the presence of a snake, an evocation of the Trinity and a compelling representation of children who, at once, make us think of innocence even though the way that they penetrate us with their eyes may make us wonder what they know.

The work is called 'The Divine' but Santiago sees it as about original sin.

In the spirit of postmodernity, and perhaps a bit like Sansom, Santiago describes the tensions and questions that sit in her work:'The Christian doctrine of original sin prompts me to examine the ideals and principles surrounding faith, creation stories, motherhood, cultural heritage and gender roles. These themes frequently inform my work, as my practice negotiates the tensions that exist within my multiple identities as a Filipina, an Australian, as a mother and as an artist.'

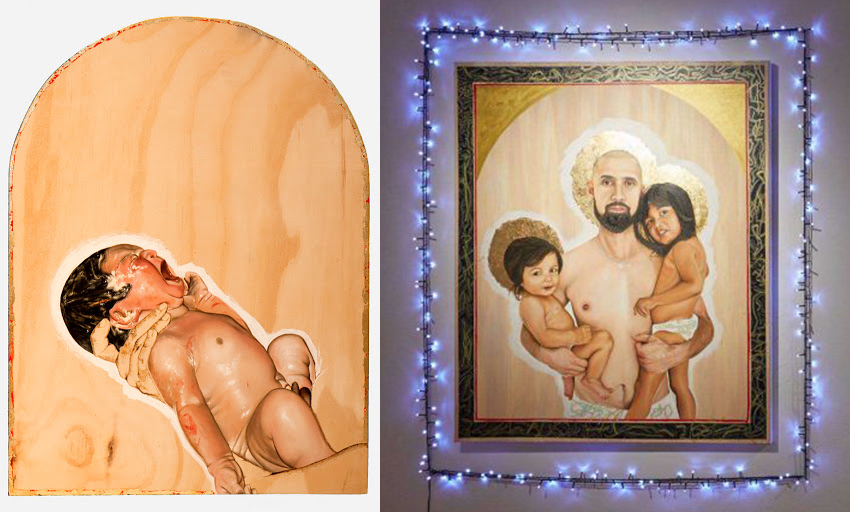

I find Santiago’s representations of herself, motherhood and family very beautiful.

Here's an image of a newborn son and, on the right, you’ll notice her husband and two of her three children in a 2017 work called 'The Father, the Son and the Panganay (firstborn).'

Not only is the painting style influenced by devotional art, when exhibited one gets a sense of a family shrine.

Santiago is a most talented artist and, if her work is saying that there is something holy in family life, if there is the image of the divine in the human, if the spark of life that creates children reminds us of God the creator, then I want to be drawn into the devotional stance of these works.

But what if the pull is in the other direction – is God a psychological projection: a father or mother writ large?

Is it too much to paint your three children and title it 'The Divine'?

The Sulman prize might represent religion as elusive fragments or personal projections and it asks us how we will paint our lives to say and picture something clear and truly transcendent: that Jesus Christ came into the world to save sinners.